For more than six years, the armed conflict in Yemen continues to exacerbate the levels of poverty and food insecurity across the country. 80% of Yemenis live below the poverty line, and 66% of the population require some form of humanitarian aid to meet their basic needs. Two out of nearly eight million people living in the southern parts of the country are estimated to be severely food insecure. Prolonged conflict, as well as high food prices, depreciation of the local currency and disrupted public institutions, including the agricultural sector, are the major drivers of acute food insecurity.

Yemen’s Abyan Delta

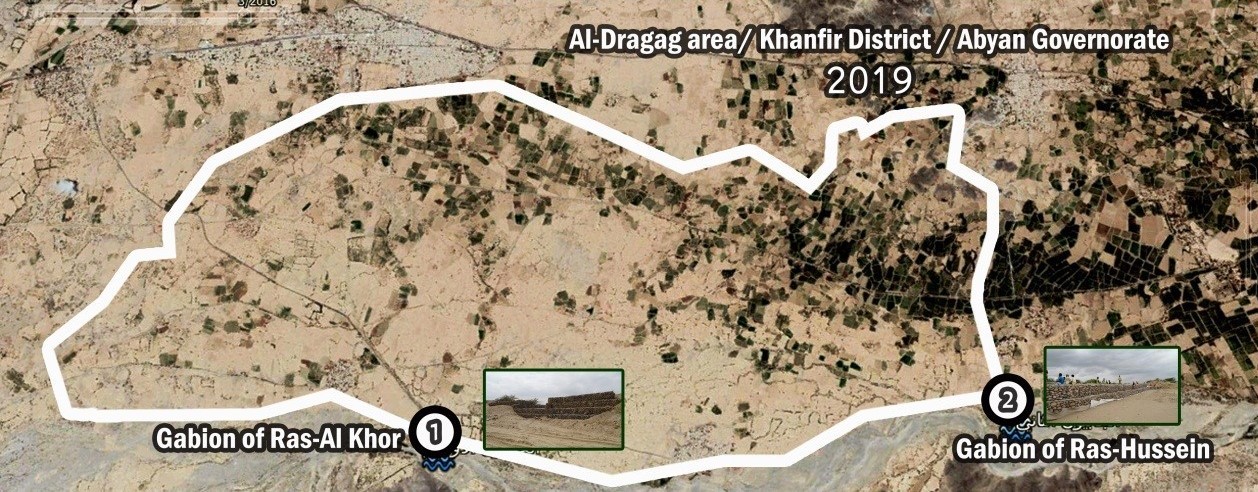

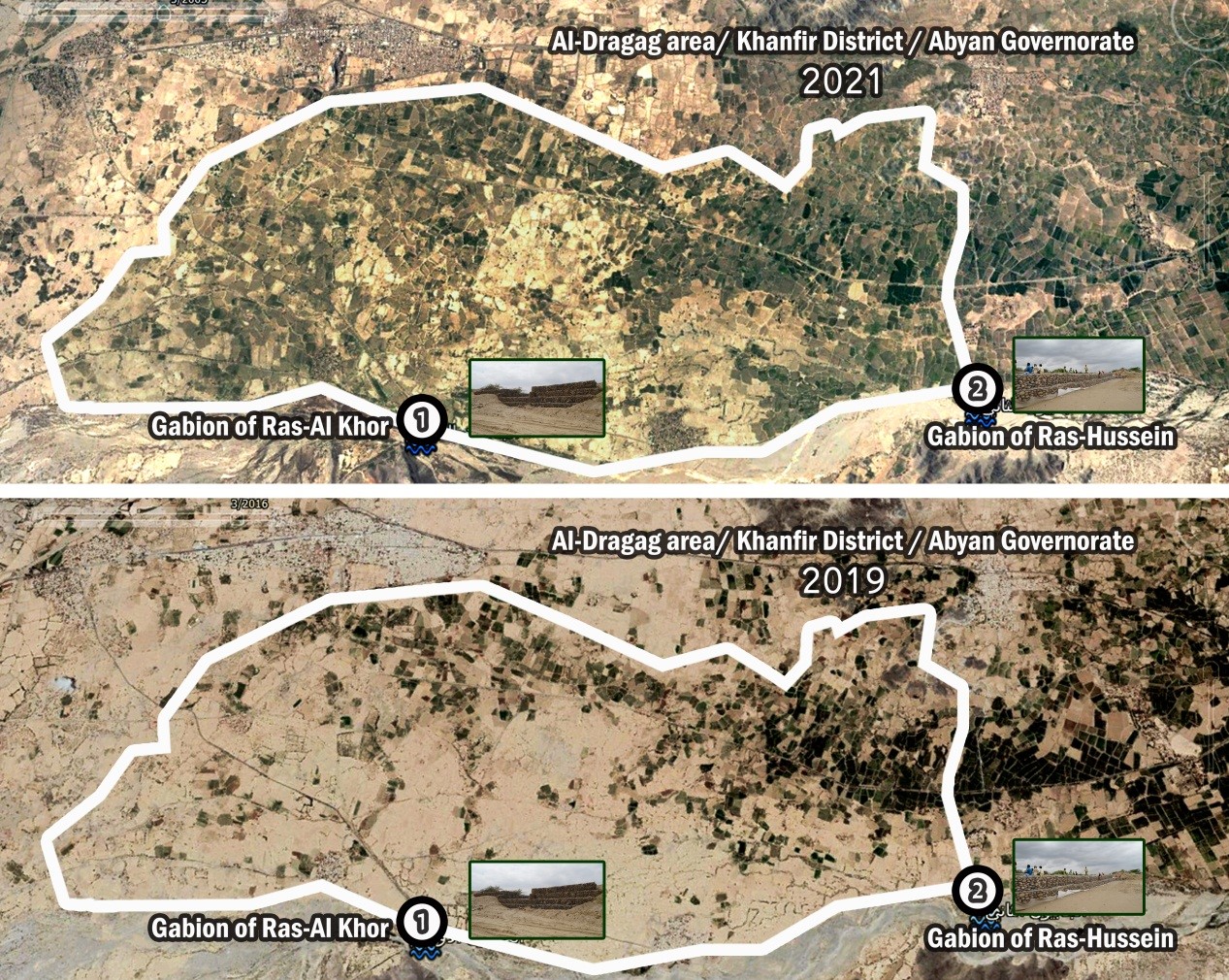

Abyan Delta is one of the most fertile agricultural lands in the southern part of the country and was once known for its excellent crops. The main livelihoods activities in Abyan are agriculture, fisheries, livestock breeding and beekeeping. Nearly half of the residents in Abyan depend on agriculture as the main source of income. Yet the conflict, together with the economic recession, have limited their access to seeds and cultivation supplies. Moreover, price instability and fuel shortages continue to impact seed quality and the availability of much-needed services such as water, transportation and electricity. Over time, many farmers abandon their farms in pursuit of alternate livelihoods.